Dizzy Gillespie

Dizzy Gillespie with Yugoslav musician and composer Nikica Kalogjera and fans. Zagreb, Yugoslavia, 1956. Courtesy of the Marshall Stearns Collection, Institute of Jazz Studies, Rutgers University.

Kool Kat Diplomat

In March of 1956, bebop trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie and his band embarked for Southern Europe, the Middle East, and South Asia on the first U.S. State Department jazz tour. For government officials eager to present a positive image of America abroad, the integrated group was a dream come true. And Dizzy, with his spell-binding virtuosity, arresting solos, and egalitarian sensibilities buoyed by playful humor, won over a wide variety of audiences, from sophisticated fans in Beirut to people in Dacca, East Pakistan, who probably had never before heard jazz. “The language of diplomacy,” argued a Pakistani editorial, “ought to be translated into a score for a bop trumpet.”

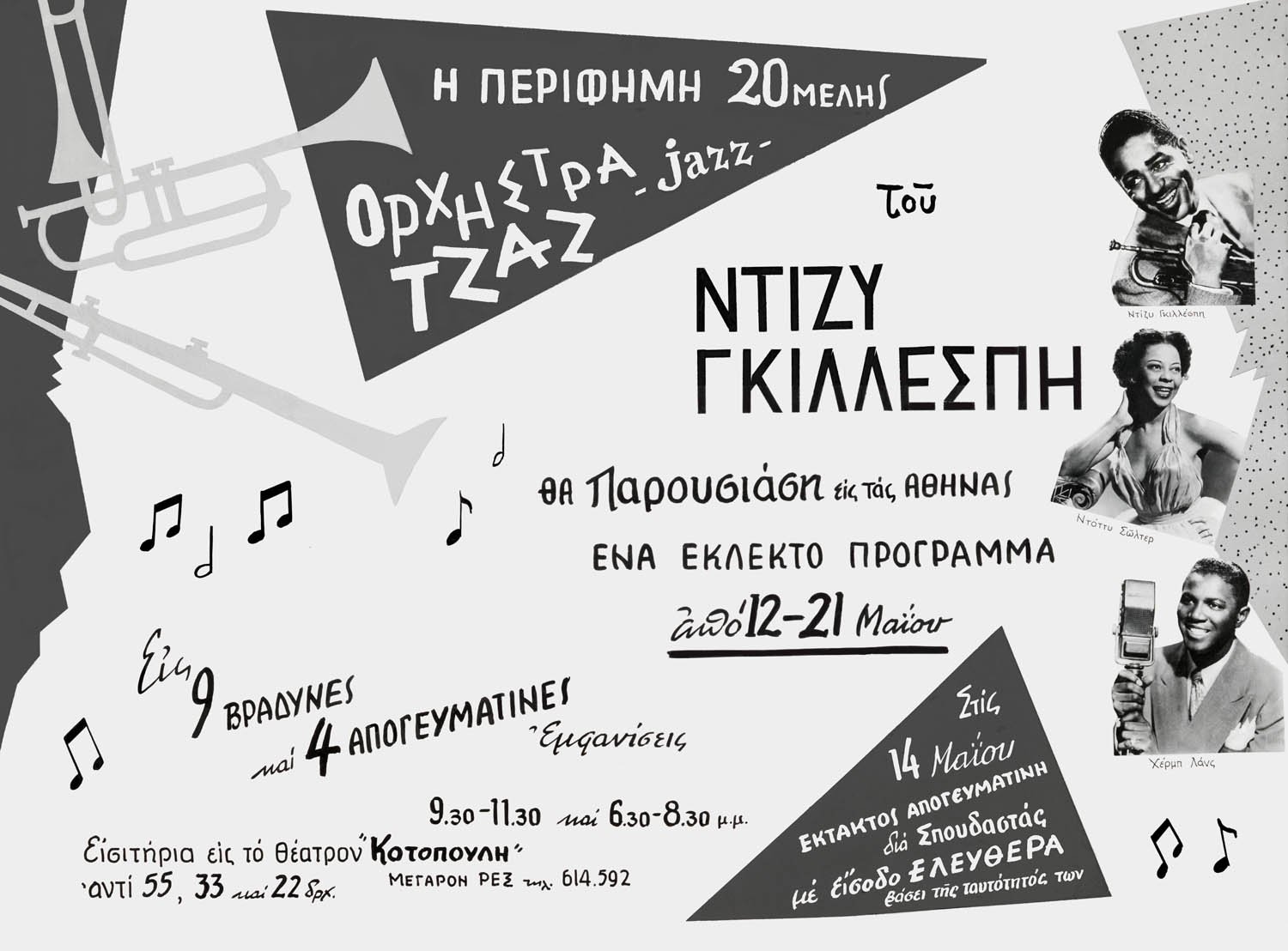

Jazz critic and scholar Marshall Stearns accompanied the band and attributed the global popularity of jazz to its anti-authoritarian ethos that transcends rules and regulations. He described the group arriving in Athens to play a matinee for students who had recently stoned the U.S. Information Service office to express their anger at America’s support of Greece’s unpopular government. In spite of the potential for disaster, the young people were so excited by the music that Dizzy later recalled they tossed their jackets in the air and carried him on their shoulders through the streets of the city.

Gillespie delighted in meeting people abroad, from children to musicians. In Karachi, Pakistan, he refused to play until the doors were open to the “ragamuffin children” because “they priced the tickets so high that the people we were trying to gain friendship with couldn’t make it.” Gillespie likewise opened the gates in Ankara, Turkey, declaring “I came here to play for all the people.” Fascinated by local musicians and eager to learn new music, in Dacca, East Pakistan, he heard a child playing a one-string violin with a clay resonator. The band leader took out his horn and wrote down every note, and then invited the young boy to a jam session. In Karachi, Dizzy joined a snake charmer and played for a cobra, while in Ankara he included Ahmed Muvaffak Falay, Turkey’s number one trumpeter, in the concert.

Gillespie and his band traveled to South America in July of the same year. He had long been interested in Latin jazz and was thrilled to visit different regional samba schools and play with an array of percussion instruments from the berimbao, to the cuica, and the tambourine. In Buenos Aires, Dizzy encountered the jazz pianist Lalo Schifrin who told him about the bossa nova movement in Brazil, and later met the creators of that musical style, João and Astrud Gilberto and Antonio Carlos Jobim.

Dizzy made his final State Department tour in 1973 when he traveled to Nairobi, Kenya, to perform at the celebrations of the 10th anniversary of Kenyan independence. He touched local audiences with his composition Burning Spear, written in honor of President Jomo Kenyatta, and by addressing his audiences in Swahili. In Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, State Department officials marveled at the Gillespie band’s “openness, sincerity, friendliness, and approachability” and were delighted that the great jazz diplomat had fans “dancing in the aisles.”