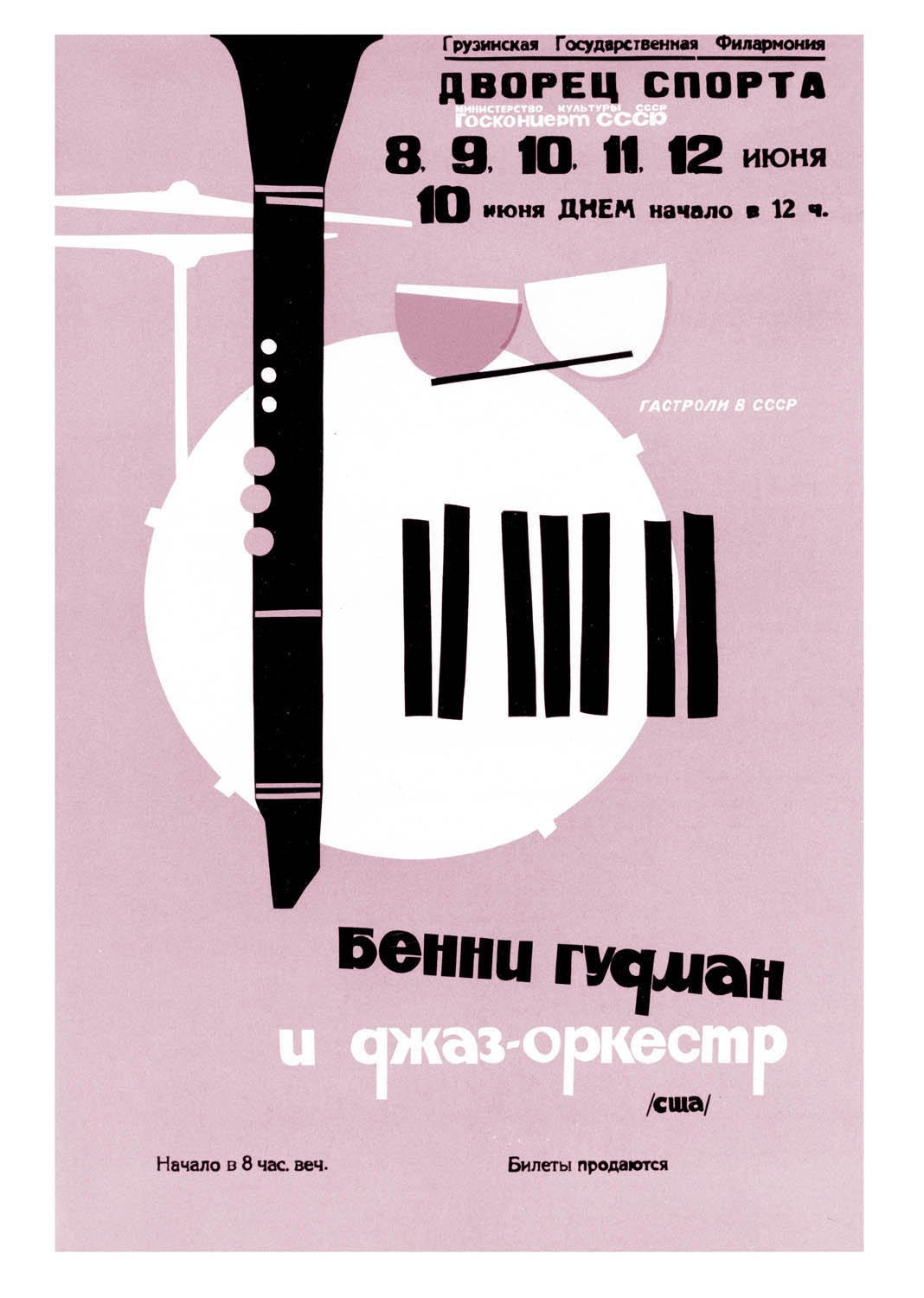

Benny Goodman

Benny Goodman takes the USSR by storm. Moscow, Soviet Union, 1962. Copyright 1962 by Bill Mauldin. Courtesy of the Mauldin Estate. Courtesy of the Irving S. Gilmore Music Library, Benny Goodman Papers, Yale University; Courtesy of the Irving S. Gilmore Music Library, Benny Goodman Papers, Yale University. Photograph by United Press International.

The Ambassador of Swing

Clarinetist Benny Goodman and his orchestra began their first State Department tour in late 1956, and performed in countries including Thailand, Burma, Cambodia, Malaya, Japan, Singapore, South Korea, and Hong Kong. The greatest diplomatic triumph of the trip came as he befriended and played with Thailand’s King Bhumibol Adulyadej, an accomplished jazz saxophonist, clarinetist, and trumpeter. The Thai King was elated to have the King of Swing join his regular jam sessions at the palace. With their warmth and deep interest in local music, Goodman and his band won over Bangkok audiences, and the New York Times reported that they established the “closest bonds of understanding” by making “a circuit of the nightclubs and dance halls, jamming with the local musicians.” Goodman also brought his diplomatic charm to meetings in Japan with Crown Prince Akihito and his siblings, and in Burma with U Thant, a future Secretary-General of the United Nations. U.S. government officials argued that the “tour strengthened the impression that America is not only great in modern plumbing and fancy cars, but in things of the spirit and the arts.”

In 1962 Goodman became the first jazz musician to tour the Soviet Union for the State Department, when he made thirty appearances in six cities during a five-week voyage. These occurred between the Berlin Crisis of 1961 and the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 at the height of Cold War tensions. Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev attended the band’s opening night in Moscow and was welcomed with Let’s Dance and Greetings Moscow, a number based on a Russian folk song. Khrushchev later sent Goodman a note reporting that he had been “very pleased and delighted to be at the concert.”

Although Soviet policy had long declared jazz a decadent modern art form, Goodman and his orchestra discovered thousands of underground and knowledgeable fans. Since Russian officials had banned the American musicians from fraternizing with ordinary citizens, band members Phil Woods and Zoot Sims made contact with enthusiasts who called out to them from behind trees and bushes as they walked through Moscow parks. For his part, Goodman surprised the Soviets with an impromptu solo clarinet performance in Red Square. The New York Times noted that he became a visiting “Pied Piper” for curious children who swarmed around him in the shadow of the Kremlin. When Benny saw a squad of soldiers marching stiffly by to relieve the guard at the Lenin Mausoleum, the temptation was too much for him and he broke into a rendition of Pop Goes the Weasel. He then “caught the rhythm of the passing boots and the King of Swing kept time with the Red Army.”

Leningrad was the undisputed high point of the Goodman tour. Phil Woods befriended a local saxophonist and a pianist, starting an international jam session. On opening night at the Winter Stadium the band played forty minutes of encores. For the final concert the audience remained after the last song, cheering and demanding more music. Over an hour after the performance ended, Goodman came on stage in a sweater and slacks and played a solo.